On May 19, Sarah Amsler (School of Education/RiCES, University of Lincoln) and Ana Cecilia Dinerstein (Social and Policy Sciences, University of Bath) gave a talk at the ‘Utopias, Futures and Temporalities: Critical Considerations for Social Change’ conference, organised at the Bristol Zoo by AHRC researchers in the Connected Communities and Care for the Future programmes. Marking the quincentennial of Thomas More’s Utopia, the conference gathered researchers, educators and activists from around the world to encourage ‘reflection on the uses and misuses of utopias and dystopias in social change’ and on ‘the contribution of ideas of the future and of temporality to the processes of social transformation’. This presentation explored the role that organised hope plays in the creation of alternative futures and offered examples of the kinds of knowledge and education that are strengthening this work in prefigurative social movements in the UK and Latin America today.

‘Learning and organising hope’ (abstract)

While social futures were shadowed by warnings of the death of the utopian impulse in the latter part of the twentieth century, hope has become a prominent element in social analysis and discourses of political change since the turn of the twenty-first (Amsler, 2015; Dinerstein 2014, Holloway, 2014) This is reflected in elite state politics, such as Barack Obama’s ‘audacity of hope’ and Alexis Tsipras’s claim that ‘hope made history’ in this year’s Greek parliamentary elections; notions of hope are even more active in the many ‘hope movements’, or autonomous practices, epistemologies and struggles which aim to dismantle the institutionalized power of global capitalism in everyday life, to democratise thinking and politico-economic relations, and increasingly to construct radically different forms of social life (Dinerstein and Deneulin 2012). In the academy and amongst organic and public intellectuals, a new scholarship of this politics of possibility has begun to emerge through the documentation and theorisation of these movements.

Despite this presence of hope as an emerging field of inquiry and orienting concept for political mobilization, however, competing discourses of hopelessness, despair and paralysis pervade everyday life in capitalist societies and are particularly oppressive in contemporary states of autocracy and austerity. Many people experience the distance between the extant conditions of their lives and the alternative future that they would like to build as an unbridgable chasm, or regard their futures as relatively closed. Their fears about the nature and extent of work that is required to change this situation are exacerbated by common-sense understandings of hope as wishful thinking for a demonstrable result within existing rhythms and parameters of possibility, rather than as a critical and active relation to what Paulo Freire (1970) called ‘untested feasibility’. This generates backlash against the politics of hope in favour of adaptive or pragmatic agency – which, in situations where sustained radical change is needed to ensure future and better possibilities, only reinforces the experience of impossibility. Such untheorised politics of hope do not, in other words, underpin critical forms of anticipatory consciousness or action.

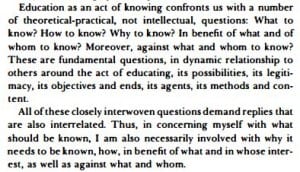

In this paper, we translate our recent research into conceptual tools which can be used to unblock this impasse and activate the power of hope for sustaining emancipatory movements, and argue that ours is a dialectically auspicious moment for what Ernst Bloch (1959) once called ‘learning hope’. Drawing on epistemological and political insights from autonomous movements and critical pedagogies, we demonstrate how hope can be theorized as an epistemological relationship to human and social change, a ‘directing act of a cognitive type’ and a method of critical thinking and action, and illustrate how these theorizations can inform pedagogies of hope that facilitate ‘possibility-enabling practices’ and ‘alternative-creating capacities’ (Amsler 2015, Dinerstein 2014). While methods and pedagogies of hope are multifaceted, in this paper we focus on elucidating the character of hope-time (in comparison with domination-time) and theoretical and empirical methods for recognizing and intervening in hope-time. From this theoretical work, we finally introduce some concrete tools for educating and organizing hope to activate and sustain radical being in both social movements and everyday political life. These tools can be used to make ourselves aware of the unfinished and open nature of the world and the necessity of daydreaming individually and collectively. Above all, they enable us to design a new approach to reality that does not take it for granted and rely on ‘facts’ but that engages with the other realities, the realities of the not yet that already lurks in the present and required to be imagined.

References

Amsler, S. (2015) The Education of Radical Democracy, London: Routledge.

Bloch, E. (1995) The Principle of Hope, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bohm, S., Dinerstein, A. C. and Spicer, A. (2010) (Im)possibilities of autonomy: social movements in and beyond capital, the state and development. Social Movement Studies, 9 (1), pp. 17-32.

Dinerstein, A. C. (2014) The Politics of Autonomy in Latin America : The Art of Organising Hope.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dinerstein, A. C. and Deneulin, S. (2012) Hope movements: naming mobilization in a post-development world. Development and Change, 43 (2), pp. 585-602.